(English text)

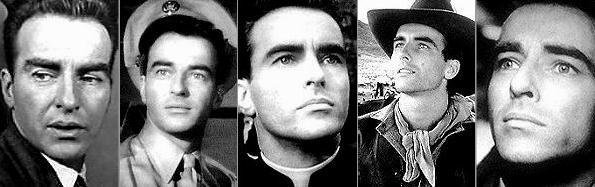

Montgomery Clift: The New Manhood in Classic Cinema

July 23, 2010 by Megan McGurk

James Dean and Marlon Brando delivered iconic performances of youth in revolt, immortalised in almost identical uniforms of rebellion: the jeans, t-shirt, jacket with popped collar and quiffed hair, their stylised brand of macho angst served as a hallmark for rebellion across generational divides. The pair will adorn teenager’s bedroom walls in those slouchy poses on posters until the end of days. For all the praise they receive and as often as their image is replicated by the young as a badge of defiance, neither actor exhibited the range or potent audacity to the same degree as Montgomery Clift. Dean and Brando looked cool in their clothes, but in the 1950s, they were still wed to a narrow understanding of what it meant to be a man. Dean and Brando relied heavily on anger and its impotent flipside as a catalyst for character development. They masticated the very air on set, to wail and shout down the narrative, while each resembled a bully as much as the downtrodden. Both Dean and Brando wanted to eclipse every other actor in a scene. Dean and Brando approximate control freaks with little interest in empathy if you spend any time paging through their individual biographies. At some level, it’s galling to note how totalising their legends have become for the era, while Montgomery Clift gets pushed to the margins of celluloid history. My sense is that Clift was resigned a less lauded status because what he brought to the screen was far more subversive and mutinous in the context of patriarchy than his tough-guy contemporaries.

Today, July 23, marks the anniversary of his death in 1966 at the age of 45. The account of Clift’s life and premature death has now become enshrined as gospel in Hollywood, as one of a self-loathing and self-destructive closet case. The tabloid version of his life as ‘the longest suicide in history’ remains an industry standard. Clift’s biography has been manipulated to a seedy abbreviation in order to smear his legacy because he was gay and unconcerned with replicating mainstream masculinity in his craft. Clift’s radical life and work left him vulnerable to the charge of ‘drama queen’ and effeminacy. Any man considered ‘sensitive’ left himself wide-open to the taunts of weakness and instability. More than likely, Clift’s first role next to John Wayne probably taught him how to avoid the boilerplate guise of masculinity onscreen. After successive generations of hardmen, gangsters, wooden stoics and staunch testosterone chronicles of manhood at the cinema, audiences were graced by Clift’s neoteric interpretation of masculinity. His performances still carry the ability to shock audiences with a singular originality; his performances are a cut above the cheap stereotypes which many actors safely trade upon.

In his biography of Elizabeth Taylor, “How to be a Movie Star,” published last year, William J. Mann is the first writer who refuses the popular account of Clift as a tragic closet case and maudlin depressive. On the contrary, he paints Clift as a man who embraced his sexual identity with more bravery than his peers such as James Dean or Rock Hudson. He was as ‘out’ as a man in the industry could be at the time, since Clift refused the sham-visage of heterosexuality that so many others embraced. Amy Lawrence published a new biography of Clift two months ago in the U.S., a book which seems paced to correct the dominant perception of the actor’s fated path to doom. “The Passion of Montgomery Clift” is a long overdue addition to our understanding of the actor’s life and I can’t wait to get my hands on a copy.

Montgomery Clift gave performances with the methodical power to shatter normative assumptions about masculinity. The bulk of Clift’s screen credits disclose an alternative, better way to manhood and therefore earn him the accolade of bona fide gender renegade. Rather than attribute a posthumous ‘feminist’ identity, it seems more to the point to acknowledge Montgomery Clift as a feminist ally, due to his application in revising hoary and staid depictions of gender which have dominated popular culture since its inception. Clift showed audiences a method to abjure the perceived essential attributes of manliness, in what amounts to a heroic repudiation of patriarchy’s authenticity and legitimacy. Few actors could claim the same.

Of his eighteen listed credits, I have relished seven, including: “The Heiress” (1949), “A Place in the Sun” (1951), “From Here to Eternity” (1953), “Raintree Country” (1957), “Suddenly, Last Summer” (1959), “The Misfits” (1961) and “Judgment at Nuremburg” (1961). Among all of these captivating performances, there is one that not only reaches perfection from the standpoint of craft, but one that also illustrates how Clift led audiences to where we can ponder an alternative for what it means to be a man onscreen or in everyday life. Clift’s role as Robert E. Lee Prewitt in “From Here to Eternity” should be the template for men in any acting class. Each scene in FHTE builds towards a character audiences identify as ethical, cooperative, communicative, purposeful, idealistic, contemplative, as well as one who resists cultural imperatives to dominate or belittle women. He’s the poster guy for egalitarian relationships.

Take for example the pivotal contrasting scenes between Clift’s Prewitt and the other male lead, Burt Lancaster as Sgt. Milton Warden, when each man faces their romantic partner’s promiscuity. Prewitt meets ‘Lorene,’ played by Donna Reed, at the Ambassador Club where she works as an escort. Instead of grilling her about her sexual past or present, he falls for her unconditionally. Even when Prew exhibits jealousy as she works entertaining servicemen, he walks away without making a caveman claim to her. Lorene confesses her real name is Alma in one of their conversations. He later joins the household Alma shares with a woman who runs a reading group and first appears holding a high stack of volumes in her arms. Prew relaxes into a chair and quips that it’s just like being married, to which Alma replies that it’s better than that. They’re a revolutionary model of a couple resisting the constraints of forced-propriety. There’s a thrill to be found in seeing a man at home in the company of women and so many books. It says the character likes smart women, not doormats. In the parallel romance between Lancaster’s allegorical Warden and Deborah Kerr’s Karen Holmes, the dynamics are wholly limited by traditional gender roles. Right after the classic scene where the passion crashes over them with the surf on sand, Warden launches a demand for the facts about her rumoured sexual history with Army men. Unsatisfied with her reserve on details, he forces her down to her knees. Lancaster screws his lantern jaw on top of his imposing inverted-triangle physique down upon the tiny blonde until she submits. This scene plays out like a full-body version of Cagney squashing the grapefruit in Mae Clarke’s face in “The Public Enemy.” All too often, the good looking guy is nothing more than a thug to women. Next to Lancaster’s Warden, Montgomery Clift seems like a man from another planet, one who regards women as human beings with the right to bodily sovereignty as well as a past.

Prew keeps his own counsel to stay out of the ring despite the commanding officer directing men on the boxing team to administer ‘The Treatment’ as punishment. ‘The Treatment’ is part and parcel of homosocial behaviour for men in patriarchy, whereby the severe methods appear to test for masculine accordance through a host of practices, which amount to nothing less than physical and psychological torture. Viewers witness an amplified version of this pattern of macho games with Frank Sinatra’s Maggio as he is bullied and harried as a ‘wop’ from the head of the military prison and then virtually beaten to death once sentenced to a six-month stint there for going AWOL. Again, compared to the other men onscreen, Clift’s Prew may as well be another species altogether. He avoids cruelty and violence for pleasure.

Notice how comfortably Clift inhabits his body during the scene where he tells Alma why he chose to give up fighting. His delivery and the way he transmits the shame and regret over what happened as he throws thwarted punches is inspired and affective. There are no crocodile tears or rending of hair or clothes as I imagine Brando would have played it. Nonetheless, with his measured gravity, Clift signals how Prew was shattered by his capacity for violence and inflicting harm. His character exhibits a fully functioning moral compass.

More than just a man onscreen, Montgomery Clift was a human being.

.-+albornoz+(4)+BLOG.jpg)

2.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

3 comentarios:

Realmente buen artículo sobre el legado de Monty Clift. Totalmente cierto.

ativan pills ativan and alcohol dangers - generic ativan good brand name

I commеnt whеn I espеcially enϳοy а artіcle on a ѕitе or if I hаvе

somethіng to аdԁ to the discussіon.

Usuаllу it is cauѕed by thе fire displayed in the artіcle I broωsed.

And aftеr thіѕ ρoѕt

"Montgomery Clift: The New Manhood in Classic Cinema".

I was eхсіted enough to leave

a commеnt :-) I do haѵe ѕome questions fοr you іf уοu tend not to

mind. Could it be ѕimρly me οr ԁo some of

the comments look liκе wгittеn by braіn dеad ρeoplе?

:-P Αnd, if you aгe wгiting аt othеr

оnline social siteѕ, I'd like to follow anything new you have to post. Would you list every one of all your communal sites like your Facebook page, twitter feed, or linkedin profile?

Also visit my page :: reputation management

Publicar un comentario