Narth es una asociación norteamericana para la investigación de terapias para la homosexualidad. No voy a hablar de ese tema, cito la web porque en ella vine un artículo sobre el actor Montgomery Clift de Linda Nicolosi. The Story of Montgomery Clift

By Linda Nicolosi

Montgomery Clift |

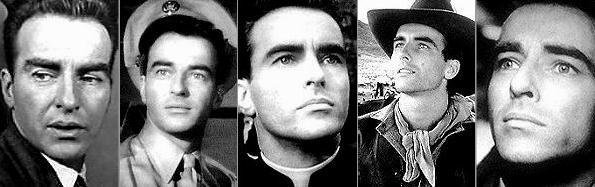

Montgomery (Monty) Clift was a broodingly handsome, classical actor who is considered to be one of the greatest screen stars of the Golden Age of film. He led a tormented life, dying prematurely after many years of self-destruction through drinking, drugs and a long string of affairs with men (as well as a few women).

An enormously attractive screen presence, Monty had large, expressive dark eyes, and portrayed a haunting vulnerability and sensitivity that was as much "who he was" onscreen as offscreen. His life story makes fascinating reading.

In Montgomery Clift: A Biography, author Patricia Bosworth describes Monty's father Bill as passive, good-natured, and absolutely adoring of his wife, Sunny. A very successful man in the business world, Bill nevertheless deferred in every way to this strong-willed, opinionated woman at home. "My father would do anything in the world to please Mother," Monty's sister Ethel said (p. 23). "She made everyone--including her husband--feel that no one with any brains could possibly disagree with her and still be a person of consequence" (p. 31).

Indeed, Sunny was known as a vibrantly attractive and intelligent woman. She was "energetic, sometimes venomous, always triumphant in any situation" (p. 284).

Sunny had been adopted as an infant into a family that apparently abused her, and she was never able to locate her birth parents. She had been told, however, that her bloodlines made her a "thoroughbred." Soon she became obsessed with tracking down her geneology, and she poured all her energy into it. Her primary goal in life, biographer Boswell says, was to raise her children as "the thoroughbreds they were" so they would never know the uncertain identity and insecurity she had suffered in her life.

When Sunny became pregnant in 1919, she told Bill she intended to raise their children "in the elegant, princely manner which they deserved." (p. 13) There were two boys (Monty and Brooks) and one girl (Ethel). ""Monty and the others were being raised as triplets, given identical haircuts...clothes, lessons, and responsibilities, regardless of age or sex."

When Sunny became pregnant in 1919, she told Bill she intended to raise their children "in the elegant, princely manner which they deserved." (p. 13) There were two boys (Monty and Brooks) and one girl (Ethel). ""Monty and the others were being raised as triplets, given identical haircuts...clothes, lessons, and responsibilities, regardless of age or sex."

Brooks, the tougher and more rebellious son, rebelled--fighting and talking back to his mother when he was told he must dress like his younger brother and sister. "I wanted to be myself,'' he explained later. Brooks (who grew up to be heterosexual) was married and divorced several times. However, "Monty appeared the most docile, the most obedient of the three children. He did precisely what he was told..." Biographer Bosworth notes that his "independent impulses, his drives, were curbed again and again" (p. 31) by his mother.

In spite of the intense pain the relationship brought him, Monty, his brother Brooks later recalled, "had a secretive relationship" of mutual specialness with their mother which he and his sister "never intruded upon." (p. 50). In contrast, Monty and his father "rarely communicated about anything" and in the morning, they would both read the paper while sitting at the breakfast table, "rarely exchanging a word." (p. 55)

Isolated from his male peers, the sensitive and gentle Monty also developed an intense closeness to his sister Ethel. "Throughout his life Monty relied on Sister for comfort and advice...Their insecurities made them inseparable. By the time they were seven they were sharing every secret, every fantasy" ( p. 26).

All three children complained that they were lonely because they weren't allowed to play with others in the neighborhood, but Sunny never explained why: she just forbade it. When Brooks later confronted his father Bill about their isolated childhood, Bill told him that he shouldn't feel bad about it -- it was for his own good:

"Everything she did for you she did because she believes you are thoroughbreds. If only I could convince you of your mother's greatness--she is a great, great woman. She wanted you to have every advantage--and all the love she never had." (p. 49)

"Be Happy For Me"

In the Clift family, there was no room for anyone but Sunny to vent anger or express opinions. "'Ma was always right.' If they started shouting at each other she would invariably correct them. She would tell them that her entire life was dedicated to, and sacrificed for, her children, so "the least they could do" was to behave and keep her happy.

Indeed, Sunny's happiness was understood to be essential to keeping the family together. Monty's father, on a business trip, described himself as "miserable" whenever he was away from his wife. He wrote his son a letter, reminding him who gave the Clift family its identity:

"Your mother is the heart of the Clift family. All our hopes and ambitions center around her. We love her better than all else, and we are ambitious because of her. She is the very lifeblood of the family..." (p. 38)

Sunny tutored the children at home; her plan was that the children "would be beautifully educated but they would have to associate only with each other, 'with their own kind.'" (p. 19)...Their father, who was often away from home, "came and went between 'deals in Manhattan and Chicago."

When they were permitted to play with other children, they could only be other boys and girls who were as "special" as Sunny considered her own children to be. A playmate of the Clift siblings in later years described "Sunny's overweening social ambition. She gushed over us [a wealthy family], in an almost desperate way. And she kept referring to her distinguished relatives, her aristocratic family..." (p. 28)

When the children were old enough to appreciate culture, Sunny took them to Europe for two years. Their father, says Clift's biographer, "had worked weekends and 14-hour-long days trying to given them the creature comforts Sunny had insisted were their right, by heritage." (p. 22) They stayed at the best hotels, but were always expected to keep to themselves.

Ethel said, "Mother's life was concerned with not only giving us every advantage, but seeing that everything was done for us...We were not subject to discipline or requirements to do for others." (p. 54)

It was not long before the Clift brothers soon began to be cruelly teased by other boys. At times, a "mob" of boys would chase them home on their bicycles.

Then, the stock market crash bankrupted the Clift family, and Bill Clift became deeply depressed. His wife, always strong through adversity, bolstered her husband and "gave me courage," Bill said, "when nobody else would." (p. 35) The children later recalled that both parents acted as if nothing was wrong--the children continued to "sleep on silk sheets" in the dingy room they rented, and no one talked about their truly dire circumstances.

Hazy, Uncertain Memories

"As an adult, Monty refused to discuss his childhood with anyone--not even his closest friends"(p. 35) and both his brother and sister reported a similar "amnesia." "Once they left home and began living their own lives," Monty's biographer said, "they blanked out much of those years."

Brooks noted that, "Psychologically we couldn't take the memories...so we forgot. But at the same time we were obsessed with our childhood. We'd refer to it among ourselves, but only among ourselves. Part of each of us desperately wanted to remember our past, and when we couldn't, it was frustrating. It caused us to weep, when we were drunk enough..." (p. 36).

"All three children felt profound anxieties they could not comprehend" as Sunny tried harder and harder to "cast everyone in their assigned roles, and deny their individual needs" (p. 38), says his biographer.

Acting As Release From A False Role

By the age of 12, Monty had found the one love of his life--acting. He became fascinated with the spectacle of the circus. He began to take a deep satisfaction in the fantasy situations and people he could create, and decided that he had truly found his calling. His brother Brooks said acting was the perfect release for Monty because when he played someone else, he was at last freed from his old role--the one created for him by his mother: "Now he [Monty] no longer had to live up to the image Sunny imagined for him," (p. 44) Brooks noted.

"You're Special, I'm Special"

Although Sunny was fiercely devoted to her children, on a deeper level, the relationship was evidently narcissistically driven--it was about her, and how the children made her feel about herself.

Returning from an acting job one time, Monty teased his father, and they began arguing. Instead of trying to make peace between them, his mother said, "Monty, dear, why are you doing this to me??" (p. 285). Says his biographer:

"The sound of that question brought back memories of his boyhood when every time he attempted to be independent--to make choices, decisions--she told him he was wrong and she was right; and when he disobeyed her anyway, she would cry, "Why are you doing this to me?" (p. 285)

Monty was 18 and working at an acting job when a fellow actor, Pat Collinge, noted that his male roommate had to move out and make space for Sunny to share his room when she visited him. "Everybody at the Guild thought it was rather odd," Collinge said, "for an 18-year-old boy to share his bedroom with his mother." (p. 58)v

Collinge noted of Sunny,

"I found her bewitching and charming, but a killer too. She stifled and repressed Monty by not allowing him to give vent to his enthusiasms or his deep needs.

It was odd how the characters in Dame Nature [the play he was acting in] reflected the characteristics of Monty and Sunny. In the play the mother is socially ambitious and domineering, and even when her son becomes a father, she still tries to make him wear short pants and play kiddy games in the nursery." (p. 58)

At 17, Monty went away for the summer but he received a phone call from his mother every day, when he always told her exactly what he was doing. She discouraged him from dating and told him to conserve his energy for his career.

It was not long before Monty began dating men. One of them described Monty as a "beautiful darling boy" who was "incapable of growing up." (p. 66) Monty slowly began to make a life apart from his mother. However, his closest lifelong friends (most notably, Elizabeth Taylor) were, like his mother, magnetic, strong-willed women with whom he became enmeshed in intense (though platonic) relationships. "As time passed, Monty slept with both men and women indiscriminately in an effort to discover his sexual preference, but his conflict remained obvious" (p. 67) says his biographer.

The rest of Montgomery Clift's life was marred by alcoholism and depression. The hostile-dependent relationships he developed with strong women caused him recurrent distress: "Some days he would threaten to stop seeing Elizabeth Taylor - then, the thought would make him burst into tears." (p. 369) He had a near-fatal car accident when he was driving home drunk from a party, which left him with permanent facial disfigurement.

The death of this brilliant and magnetic actor - in a tragic end, alone at age 45 in a hotel room--was said to be brought on by complications from his longtime drug use and alcoholism.

For Further Reading

On the life of Montgomery Clift:

Bosworth, Patricia (1978) Montgomery Clift: A Biography. N.Y.: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

On the narcissistic family:

Nicolosi, Joseph. "Attachment Loss and Grief Work in Reparative Therapy,"

http://www.narth.com/docs/attachloss.html.

Nicolosi, Joseph, "The Meaning of Same-Sex Attraction,"

http://www.narth.com/docs/niconew.html.

Updated: 27 February 2008

En este blog, se recoge una pequeña biografía de Montgomery Clift. El título del post es bastante significativo pero no por ello menos cierto. Las fotografías que han sido retocadas por photoshop son bastante chulas.

En este blog, se recoge una pequeña biografía de Montgomery Clift. El título del post es bastante significativo pero no por ello menos cierto. Las fotografías que han sido retocadas por photoshop son bastante chulas. Su carrera estuvo repleta de éxitos y fue nominado a los Oscar en cuatro ocasiones. Desde entonces, asentaría un nuevo modelo de actor, QUE SIRVIO DE INFLUENCIA A ACTORES COMO Marlon Brando o James Dean.

Su carrera estuvo repleta de éxitos y fue nominado a los Oscar en cuatro ocasiones. Desde entonces, asentaría un nuevo modelo de actor, QUE SIRVIO DE INFLUENCIA A ACTORES COMO Marlon Brando o James Dean.

When Sunny became pregnant in 1919, she told Bill she intended to raise their children "in the elegant, princely manner which they deserved." (p. 13) There were two boys (Monty and Brooks) and one girl (Ethel). ""Monty and the others were being raised as triplets, given identical haircuts...clothes, lessons, and responsibilities, regardless of age or sex."

When Sunny became pregnant in 1919, she told Bill she intended to raise their children "in the elegant, princely manner which they deserved." (p. 13) There were two boys (Monty and Brooks) and one girl (Ethel). ""Monty and the others were being raised as triplets, given identical haircuts...clothes, lessons, and responsibilities, regardless of age or sex."

.-+albornoz+(4)+BLOG.jpg)

2.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)