By Carter B. Horsley

The non-nonsense swagger, good looks and long career of John Wayne made him the most famous male movie star of the 20th Century and a major icon of American culture.

He was the quintessential quiet but strong leading man who was given more to force than words. Widely imitated and parodied, Wayne's success was based on his persona as a "he-man hero" without peer. His early reputation was based mainly on his glamour and he achieved major stardom in "Stagecoach," a 1941 western, after about a decade of work mostly in minor westerns.

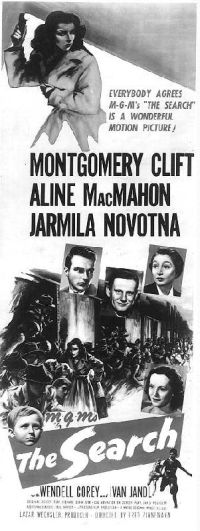

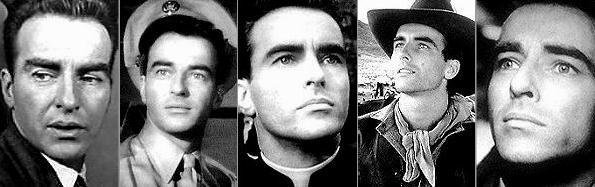

In this film, Wayne portrays Tom Dunson, a troubled, embittered and mean rancher who loses the respect on a cattle drive of his fellow cowboys and his adopted son, Matthew Garth, who is portrayed by Montgomery Clift in his screen debut. Wayne's portrayal of Dunson demonstrated that he could be a very good actor for he ages admirably in the film and his performance is memorable not only for its strength but also its subtlety.

While the movie is far from perfect, it is extremely interesting in its pairing of Wayne and Clift in the leading roles. Clift is quite wonderful. He is cocky, sensitive, tortured, romantic, headstrong, uncertain, fearful and respectful, and very expressive, all qualities that James Dean would embody a few years later in his brief but stunning career. Clift's persona is rather poetic whereas Wayne's is titanic and bold. Both are highly mannered but in very different ways.

Wayne is simple and brutish. His walk/saunter is that of a determined, possessed, focused man.

Clift is more dimensional. His hesitatations, ponderings and waverings are that of a sensitive, reflective, idealistic individual.

Their characters, however, are not black-and-white. Clift is agile with his gun and no coward. Wayne may not hesitate to shoot someone, but will honor them with a "reading" over their grave.

Many critics and reviewers have commented that the film's "love interests," initially Coleen Gray for Wayne and later Joanne Dru for Clift, slow the film's momentum. They are, however, necessary as Gray's death early in the film helps the viewer sympathize with Dunson's bitterness and lack of humor and Dru's appeal to Dunson to spare Matt's life after he has led a mutiny of Dunson's men and expelled him from the cattle drive is a quite remarkable and surprising scene in which her willingness to sacrifice her love of Matt by agreeing to give Dunson an heir is as startling as Dunson's request. Dru, a very beautiful brunette who would appear in other Westerns with Wayne, portrays a "pioneer" woman of formidable strength. She handles this scene very well and it is perhaps the finest in Wayne's career. When Matt first encounters Dru, she has been wounded in her right shoulder by an arrow during an attack by Indians on her wagon train. The scene is quite surreal as she asks Clift many personal questions while he is shooting at the attacking Indians. Many reviewers have scoffed at the scene's incongruous dialogue, but it is one of the film's surprises, which is needed because of its quite slow beginning. We take most of the clichés of the Western genre in stride and because this film used many as well as setting many the scenes with Dru are jolting, but they serve the purpose of making the drama much more interesting as well as giving a pre-politically correct culture a big dose of feminism.

Most critics and reviewers have been disappointed with the film's ending when Dru breaks up the "showdown" fight between Dunson and Matt with a long harangue about how much they love one another. Virtually all those critics and reviewers note that however much they are dismayed by this "happy" ending, the intensity of the film is not seriously impaired. To a large extent, they are right: Matt refuses Dunson's demand that he draw, but after being punched about he does fight back, although the viewer suspects that Matt would not kill Dunson under any circumstances and Dunson's march on foot through a herd of cattle suggests that nothing will dissuade him from revenging Matt's mutiny. In retrospect, however, the ending fits well with the scene in which Dru appealed to Dunson to spare Matt. Dunson has been humiliated and humbled by Matt, the presumptive heir to his empire. Dunson recognizes that Dru is a remarkable enough woman to ask her to have his child. He has raised Matt for about 15 years and clearly had come to love him.

Wayne's decision to relent after her harangue is really not all that surprising. One often sees the humor, if not futility, of anger at the moment of rage. It is one of the thin lines that usually makes truth stranger than fiction. A hero encounters fear. A villain discovers guilt, or remorse, or just tiredness. Anger needs to be spent somehow and time often is a fine cure and some things that appear ultimate and vital and uncompromisable sometimes are shocked in different perspectives.

The characters portrayed by Wayne, Clift and Dru are absorbing and interesting. We are fascinated by them and their unpredictability and their maturing. Our interest in them is also supported by its focus on people's often misplaced hope that other people can change their personality.

This epic Western film is about the first cattle drive in 1865 on the Chisholm Trail from Texas to Abilene. Like some of John Ford's westerns, it suffers some from the rather hokey singing that would be more appropriate for a children's campfire than the rigors of a real cattle drive, and one wonders why both directors resorted to such campiness in this genre. Presumably, such scenes were included for a bit of levity and relief from the more somber realities of the stories and perhaps to appeal to a wider "family" audience, but apart from establishing camaraderie, which is not unimportant, they detract from the sweep and impact of the stories.

The American mythologizing of the "pioneer" West goes back a long ways, but this film is one of the classics that defined the genre. "Westerns" would not begin to treat Native Americans with much respect for another couple of decades and their appeal has always been the primary notion of rugged individualism in a wild and awesome physical environment. Pure lyricism, of course, rarely made for good drama. Simple morality of the good guys and the bad guys did, even though life is more complex and this film, to its credit, focuses on those complexities to a good extent.

En la web The city review aparece esta crítica de Red River (Río Rojo, 1946):

.-+albornoz+(4)+BLOG.jpg)

2.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)